Chapter2

"What is the public sector?"

Introduction to PS

definitions, principles, areas

Many experts tried to draft a univocal definition of what ‘public sector’ is and embraces. Nevertheless, being such a vast and broad concept, there is still a variety of fragmented and different meanings. To facilitate the comprehension of the topic, we can say that the term ‘public sector’ refers to “that portion of an economic system controlled by national, provincial or local government” which is in charge of providing various public and government services and managing public enterprises.

Even though its composition significantly varies by country, the public sector usually includes such services as infrastructures, healthcare, education, transportation, communication and policy-making (Schaminée, 2018) together with the ones directly embedded in government - as elected officials, politician and organizational departments.

The public sector role is to ensure those essential services that must be accessible by every citizen, to establish a benefit for the whole of society and not only for those who directly use them (i.e. prisons system). Its structure - also called ‘public ownership’ - can be shaped in diverse ways, including:

- Direct governance, financed by public funds; the administration doesn’t have any specific regulations to satisfy a successful service delivery, and decisions are taken directly by the government.

- Public companies (or ‘ state-owned enterprises); which are slightly different from the previous category in that they enjoy greater commercial freedom and must work following commercial criteria. Moreover, decisions are usually not directly dictated by the government.

- Out-tasking - also called ‘partial outsourcing’: it could be one among the public sector format.

The public sector is framed accordingly to a series of values that usually guides its functioning together with the work of civil servants. We can identify mainly seven key values that define both important actions within the organization and the approach to be followed:

1. responsiveness: there is a need for speed in facing changes and answering the community’s needs, providing at the same time good public services;

2. integrity: public sector work should always be open and transparent, without exploiting in a negative way its public power. Additionally, it should be active in searching and solving inequalities and disparities;

3. impartiality: the work of the public organization and its employees should guarantee a high level of objectivism. Implementation should be carried on without “bias, caprice, favouritism or self-interest”;

4. accountability: civil servants have to work in order to answer explicit purposes, trying to accept and forecast the effects of their actions. They also must use consciously all the resources that they have;

5. respect: the public sector and its officials should guarantee freedom and respect among people;

6. leadership: public administration should lead in a responsive way its work;

7. human rights: it’s necessary to keep a focus of citizens’ rights, also trying to improve, advertise and support them.

These values are also part of the so-called ‘bureaucracy’ and identify the attitude that the government and the community expect from all the public sector officials and leaders. The efficiency of the public sector together with its capacity to achieve specific public goals, automatically increase when civil servants follow this model of values. At the same time, failing to address these values, can lead to a citizens’ distrust toward the work of the public sector.

Unfortunately, the present often puts a strain on the respect of these values and places the public sector and its officials in front of complex, connected and difficult challenges that still need to be solved. These peculiar challenges need to be faced with new approaches since ‘classic’ and incremental methods are not efficient in this complicated panorama. For this reason, different ways to frame problems and design solutions are required and this could be possible only undertaking an ‘innovation path’.

il’s suggested reading!

Public sector innovation

reasons, type of innovations

Public sector innovation is a journey and, like every journey, in order to understand what’s happening in the present, we should go back to find the trigger points in the past. So two key questions automatically arise: What does push governments to innovate its public sector? What are the main reasons for change?

Giving a univocal and clear answer – as for everything linked to the public ambit – is not easy. But, analyzing the ongoing situation, we can list four main reasons why administrations are changing and adapting their offer:

- a period of crisis;

- citizens request for better services;

- the advent of new technologies and faster changes;

- good examples from others.

Reason 1 - a period of crisis

Thinking about the past we can notice that, somehow, we are living, again and again, similar situations since a long time: many historic events seem to be a kind of cycle. For example, we know that many countries – no matter how big or powerful they were – have faced periods of crisis which have often been overcome thanks to changes. Nowadays, many countries are living a new period of crisis, not merely economic in nature. To fight against all of this, a lot of public administrations are putting their trust in the power of innovation, and they are trying to change the public sector as a first step. Innovate the public sector means a lot of things: it means to enhance better public services, as well as improving policy making and the government organization itself. A better public sector is, of course, a synonym of fewer costs for administrations, so, together with the crisis, it is also possible to state that also money is a great push for innovation.

Reason 2 – citizens request for better services

More and more communities are demonstrating for their public rights, asking for faster and more accessible services. Governments are forced not to ignore this important voice, and many pioneer administrations are including in the innovation process citizens and other associations. In this way, they act a sort of co-design, working with users and other relevant actors to consider opinions and ideas from different perspectives, in order to create a more successful system that tries to satisfy all the stakeholders’ needs.

Reason 3 – the advent of new technologies and faster change

Today, we are living in a world in continuous development, where classic models and standard structures are not suitable anymore to answer the present requests. This general statement perfectly fits also the public sector fields: slow procedures, paper-based documents, old processes and so on, are all obsolete elements that are not working in today’s scenarios. Administrations are trying to change and improve their current offer to go hand in hand with the developing technologies, also to take advantages from their huge potential in the public field. This will also allow governments to better face the future requests, trying to anticipate scenarios and possible situations to provide solutions also for hidden public needs.

Reason 4 – good examples from others

Last but not least, another reason why governments are trying to innovate their offer is that they look at what the ‘neighbours’ are doing. Pioneer countries such as the UK, Finland, Netherlands and Singapore, represent nowadays sources of inspiration for many other cities all over the world. With their good practice in innovating the public sector, they constitute successful examples of how a country can really improve its public sector, and they provide useful instances about right methods, processes, and approaches to use.

The concept of ‘innovation’ is linked with two connected activities that are: doing something new and shaping, improving and scaling this ‘new’ to make it suitable for a specific context. Therefore, inventing something is not enough to read this action as ‘innovative’: innovation happens only when an invention is implemented until its adoption in an organization, in the market or society.

When innovation is applied to the public sector, it is possible to observe some common patterns that are:

- novelty: change implies the adoption of diverse methods and approaches;

- implementation: innovation - as previously said - cannot be just a proposal, but needs to be improved and scaled;

- impact: innovation’s objective is to enhance some values, such as efficiency, effectiveness and citizens’ satisfaction (Arundel, Bloch, & Ferguson, 2014).

Additionally, the OECD (2015) identifies three unique aspects that highlight how innovation is approached in the public sector, 1) “as a verb rather than a noun” - it focuses a lot on the whole process; 2) “as the application of concepts rather than the invention” - contextualize innovation is fundamental for its success; 3) “as a means to an end” - innovation aims at reaching real results.

Public sector innovation tries to design new public value in line to the changing society. This objective can be satisfied only changing the way the public sector currently works, involving new and different actors, putting citizens first to structure a more inclusive and open society and delivering better services. Moreover, innovation can be used by governments also to redesign current policies with better users-focus (OECD, 2017).

Adopting innovation in government it’s a difficult journey since innovation is risky and unknown and usually public bodies prefer to develop solutions in ‘secure’ environments. The present tendency is to keep old structures, trying to maintaining the status quo.

Moreover, the most significant change is that new ideas have to be generated, rather than existing proposals being improved. This goal can only be achieved by “re-thinking, re-scoping, re-designing and re-engineering the processes/procedures, services or systems of the public sector”.

The innovation journey in the public sector is living a sensible change, moving from the so-called “green-field” (where a new proposal is designed from zero), to “sustaining” (in this case a running system is enhanced) to “disruptive” innovations (where the whole system is entirely re-invented and re-designed). In fact, as soon as the public sector started to challenge and change its offer and public services delivery, innovation itself moved from the ‘secure’ green-field area towards more challenging transformation environments.

Still, a lot of doubts and confusion toward the meaning of innovation and its role in the public sector do exist. Which is the right attitude? Are there innovative activities that are better than others? Does the government have to reshape its structure to better deal with innovation?

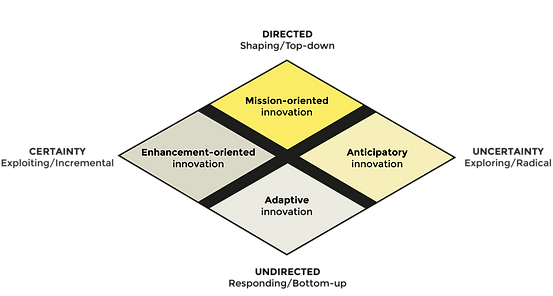

The reality is that innovation has many distinct aspects that seem very different from each other and can involve multiple actions with several goals. In this regard, the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) sustains that governments have to accept this, trying to develop a repository of approaches to take advantages from the power of innovation in the best way possible. To help this process, OPSI has recently developed a model that shows four main facets of public sector innovation:

- ‘mission-oriented’ innovation: this happens in those cases where a clear goal is set since the beginning. The achievement could be both at a local dimension or at a larger scale and is driven by a strong ambition toward the specific objective;

- ‘enhancement-oriented’ innovation: focuses on enhancing and improving methods and present approaches in order to gain better results. This facet is the one that current governments usually adopt since it doesn’t require to challenge present structures, rather it tries to exploit existing resources and models;

- ‘adaptive’ innovation: this facet is about prototyping and trying new approaches to answer new needs dictated by a transforming context. In this case, innovation is exploited to adapt to a specific ongoing change in the environment;

- ‘anticipatory’ innovation: is projected toward the future and aims at exploring and understanding emerging public issues in order to design suitable proposals. This facet can actually drastically transform current models and reshape existing structures and approaches: for this reason this specific category is strictly linked to a high level of uncertainty (OPSI, 2019).

The best scenario for impactful and successful change is the one that sees the transformation happening in the intersection between the four different facets. For this reason, it is important that governments learn and understand how to deal with all the four models, and in which specific situation one facet is more suitable than the others.

Public sector innovation needs to be supported: it is necessary to identify the right problems and translate ideas into real and achievable projects, which can be implemented, translated into other contexts and disseminated. This is only possible when the public administration is able to identify processes and structures that can support innovation at every step of its life cycle. To support this, OECD has structured an innovation lifecycle, built upon six phases:

- identifying problems: explore current issues and understand which one to solve is the first step to develop a successful proposal. The public sector is usually not good in locating challenges and opportunities of the context they are in;

- generating ideas: proposals that encourage and support innovation can both come from the community, through a bottom-up approach, or from government leaders. Usually, this implies setting some incentives to trigger a bigger ideas generation;

- developing proposals: in order to shift from concept to real proposal, it is necessary to test and prototype the ideas. As already said, innovation, by definition, is linked to newness and this obliges the public sector to deal with uncertainty, trying to change it into “manageable risk”;

- implementing projects: it is important to reiterate the proposals after the testing phase. In this way it is possible to implement ideas considering also the business side and the funds’ management;

- evaluating projects: the impact of innovative proposals must be assessed in order to understand if they are actually solving the challenges for which they were designed;

- diffusing lessons: divulging successful examples of innovation is a key activity to enable more proposals to start also in different environments.

Of course what actually matters in the reality is the perception of governments toward innovation, since they are the real drivers of change. How they want to use innovation, for doing what and what they expect in terms of impact are just some of the important points that are part of this analysis. As we can see, it is crucial to understand what the public sector thinks about innovation. One way to do that is basically studying the practical outcome of their “minds”, or, in other words, the strategies they put in place. These strategies can be profoundly different by context, but they give a clear point about the perception of governments, what they actually want from an innovative approach and how they value it (OPSI, 2017).

Additionally, in order to design successful strategies, it is crucial to bring together different key actors to trigger the innovation process. The Deloitte Center for Government Insights defined an ecosystem that presents five key roles in public sector innovation: the problem solver, the enabler, the motivator, the convener and the integrator.

The problem solver is actually the person that we identify as ‘innovator’: he/she comes up with a relatively innovative solution for a specific challenge and use methods and approaches that are typical of the design discipline (design thinking, ideation methods, innovation activities, etc.).

The second role is linked to the provision of fundamental resources to innovate. Enablers are usually the ones who organize training and sharing sessions, workshops and they also design toolkit and/or incubators and innovation hubs.

The motivator’s role is to provide incentives to encourage potential innovators to suggest innovative proposals: this is possible by establishing competitions and rewards or using a gamification approach.

The third role is one of the conveners, namely the ones in charge of bringing actors of the ecosystem together, during conferences, hackathons, jams, events, in physical spaces (such as co-working), but also in digital contexts (such as crowdsourcing platforms or other websites).

Finally, integrators represent the core of the whole system, since they are the ones who choose the actors who can potentially partner together to support an innovation process. They are also responsible for connecting and aligning them as well as keeping the innovation alive. In order to obtain a successful and responsive ecosystem, it is necessary that public organizations embrace at least two of the identified roles, accordingly to this analysis.

The roles just presented are usually embedded in government teams, whose aim is specifically to bring innovation in the public environment. Those groups can be identified as ‘dedicated innovation units’ and contribute to the transformation process in several ways that can be summarised as follows by reconnecting to the innovation lifecycle framework built by OECD (Figure1.6):

- they help the identification of the issues that primarily need to be solved, offering consequently innovative solutions to address these challenges;

- they sustain the phases of development and prospective implementation of the generated ideas;

- innovation units may also support the last two steps of evaluation and diffusion of findings from completed projects (OECD, 2017).

Figure1.6 - How innovation units can support the innovation lifecycle

Moreover innovation units can help to overcome some of the barriers this thesis is going to present in the following chapters, such as the absence of government leaders able to drive change (Boyer, Cook, & Steinberg, 2011), obsolescence and rigidities that many times characterized the public organization (Mulgan, 2014), the lack of an effective communication between governments’ departments.

Existing literature offers a vast and detailed analysis of these existing groups in support of the public sector innovation which proves how both their structures and the relationships established toward governments change case by case.

For instance, taking into consideration their assets and principal functions, it is possible to cluster them into five groups by their main purposes: support and coordination for innovative solutions, experimentation, supporting service delivery, investment and funding and networking support (OECD, 2015; OECD, 2017) (Figure1.7).

Figure1.7 - Innovation organisations: Breakdown of activities

It is fundamental to point out the fact that it is not necessarily the case that the groups follow only one of these activities: there are many examples that show how existing innovation units actually operate in a cross-functional way, uniting together more than just one cluster. Moreover, in recent years, thanks to the analysis of various innovation laboratories, it has been possible to define some elements of success, summarized in the graph below (Figure1.8).

Figure1.8 - Innovation labs: Elements for success

Looking at the history of innovation labs, an analysis carried on by NESTA and OECD shows how most of them have been established in the period between 2010 and 2014, with a sensible rise between 2013 and 2014 (Figure1.9). This increasing number demonstrated the growing interest in public sector innovation both as a concept and as an asset that modern governances want to improve and support. The research was conducted in 2014 and updated in 2016 and allowed to get an overall picture of various teams working for or within the government with a specific objective toward innovation.

Figure1.9 – A timeline of selected innovation teams and units

The same study also enabled the design of a useful model aimed at helping public organizations in the identification of the right approach and type of innovation unit to embrace during the process. The scheme considers the final goals matching them with the linked activities, the diverse kinds of groups or organizations involved, the methods used together with some actual examples of the time (Table1.1).

Table1.1 - Organisations for innovation: A typology and selected examples

To understand the results of innovation activities and their actual impact on society, the right evaluation is required and necessary. This would help to measure the efficiency of public sector decisions and to ensure the value of the public organization itself. Evaluating results in public sector innovation is a big challenge (Şandor, 2018): in fact, results usually arrive in the long-term perspective and may be spread in different parts of a specific context. Additionally, the evaluation of outcomes in this field is usually done in terms of quality and subjectivity, so defining common patterns and similar parameters of analysis is hard. The academic world is trying to accelerate and support the research of standard for effective evaluation. For instance, the “Trends and Challenges in Public Sector Innovation in Europe” (2012), taking in consideration some successful cases of innovation in the EU, has recognized six main application fields where innovative approaches reached a successful result. These six common patterns have been mapped together to identify common success factors and the lessons learned through the process (Table1.2).

Table1.2 - Success factors and lessons learned of Public Sector Innovation in the European Union

Limits & barriers

obstacles toward innovation

As already mentioned, the public sector is closely linked to its reference context. The same applies to the limits and barriers that slow down - and sometimes block - innovation. Nevertheless, today's existing searches define a series of recurrent patterns when dealing with this topic.

Although there are different views and opinions, these barriers usually involve:

- problems of budgets and the absence of clear future plans;

- lack of capabilities in dealing with any kind of transformation processes;

- a little number of stimulus that promotes innovation;

- different levels of constraints;

- over-dependence on present innovation approaches;

- reticence to face failure;

- risks reluctance culture;

- delivery pressures and administrative burdens (Albury, 2005).

Primarily, the shift from green-field to breakthrough innovation, represents the first cause of some big challenges for current governments. In fact, developing radically new solutions implies the questioning of values rooted in society and moving from supporting existing alternatives to challenge them. Moreover, while innovating, the public sector should also provide continuity in the service it delivers and sometimes keeping these two separate assets requires a big organizational effort by the public organization (OECD, 2017). Analyzing the recent trends in public sector innovation, OECD provides a clear mapping of the main barriers that Governments face when dealing with innovation along the so-called ‘innovation lifecycle’ that are summarized in the figure below (Figure2.7).

Figure2.7 - Barriers to innovation across its lifecycle and related policy tools - source : OECD elaboration

Recurrently, rules and processes are presented as one among the main obstacles to innovation -particularly in the public sector - and are usually associated to the terms “red tape” and bureaucracy (NESTA, 2012; OECD, 2017). The first relates to that set of bureaucratic proceedings “that are seen as unnecessary, duplicative, or wasteful, thus contributing to delays and creating a sense of frustration” (Schultz, 2004). While “bureaucracy” actually represents both internal organizations’ norms, and also the attitude they activate and trigger. It comes from certain values that different societies want to keep alive such as “rational decision making, integrity, effectiveness, efficiency, transparency, accountability, fairness” (OECD, 2017; Peters, 2003).

From this initial distinction, it is already clear how nowadays there is a common misunderstanding of the concept of bureaucracy, that is usually perceived in a negative way. In fact, there are not enough empirical studies or researches that prove how effectively the aforementioned set of rules inhibits innovation. On the contrary, characteristics and values typical of bureaucracy still enjoy a broad consensus both from the government and from citizens (OECD, 2017). What actually represents a barrier to change is bureaucracy dysfunction, which may occur when rules are outmoded or too rigidly enforced. Moreover, bureaucracy is also interpreted by some experts as one among three different ways to organize the public sector, together with market and relationships. At the beginning of the 20th century, Max Weber predicted the future dominance of bureaucracy above the others, due to its strong ability to organize complex systems. Thus, envisaging cutting red tape out of modern society, would represent a fault (Muir & Parker, 2014).

Despite everything, some aspects of bureaucracy might actually interfere with innovation: 1) continuance approaches against risk acceptance, 2) specialization versus departments collaborations, 3) hierarchy versus shared responsibility and 4) expertise against multidisciplinary skills (OECD, 2017).

Another recurring concept among limits and barriers of public sector innovation is ‘complexity’ that has been largely treated by scholars, particularly in terms of theories. For instance, in 2008, Klijn explained the complexity theory as “the idea that the whole (the system) is more than the sum of its parts (the individual agents) while at the same time developments of the whole stem from the (interaction of the) parts. Complexity theories stress that systems tend to develop non-linearly and are subject to various feedback mechanisms. They are also dominated by self-organisation and usually co-evolve with other systems”.

Some peculiarities of complexity strictly linked to the structure of present societies are:

- connectivity and interdependence: in complex systems as the public one, one actor could trigger an unexpected reaction on others;

- evolution: still in a networked way, the system is able to adapt and change;

- self-organization: not everybody acts in societies only following his designed role;

- emergence: the possibility that the interaction between single parts of this complex system, creates new structures;

- feedback processes: non-linearity of feedback process in society (Muir & Parker, 2014).

Many times, from the civil servants’ perspective, there are some particular aspects that inhibit the development of new proposals and mandate standardized rather than innovative solutions. These barriers are for example “cost-based budgeting and departmental structures, to audit and accountability processes, as well as a lack of career rewards” (Hallsworth, 2011). Additionally, there is a common resistance to undertake paths of change, and a small number of elements aimed at fostering innovation than not to.

The same barriers can sometimes also represent the drivers that push innovation. Still starting for the perspective of public servants, León, Simmonds and Roman presented in 2012 an analysis on this topic, organizing these drivers into internal, external and political factors (Table4).

- The internal ones are those that exist within the limits of the public organisation itself. They can involve issues among the different departments or the public sector staff, hostile behaviors, internal fights, difficult coordination, lack of continual enthusiasm, resistance to the adoption of new technologies or managerial methodologies and the absence of adequate plans. Furthermore, existing studies have found that the reluctance to start working in different ways and change the personal approach is among the most spread reasons that slow down innovation in the public sector. The whole amount of internal constraints can be clustered into “human resources-related factors, including education and training schemes to public servants, availability of incentives to innovate, and good management and leadership and bureaucracy and organisational structures and design” (León, Simmonds, & Roman, 2012).

- The second category of drivers and barriers regards the external ones, the ones that belong to the surrounding environment. They can involve periods of crisis, increasing demand for better services delivery by citizens and companies, distrust toward the public administration, scepticism and public opposition and the absence of innovators in the ecosystem. However, a large number of civil servants who collaborated to the collection of these data interprets the external environment mostly as a stimulus to innovate, rather than a constraint.

- Finally, the third group is one of the political barriers, those ones that concern policies and, more generally, political decisions and orientation. They can also include budgeting issues or lack of funds and resources, as well as barriers coming from new rules or different political parties. Modern researches in the USA present also as potential drivers/barriers elections, political board renovations and pressures coming from the same politicians.

Table4 - Internal, external and political drivers and barriers to Public Sector Innovation

Design opportunities

role of service design, chances

For what concerns the role of service design, the author will refer to two different academic sources analyzed in the previous Chapters of this thesis (see Chapter 1 & 2). Firstly, going back to the public sector innovation ecosystem designed by the Deloitte Center for Government Insights, it is possible to link the role of service designers with three out of the five presented by the study. In fact, service designers are the main ‘problem solvers’ of the system, the ones who actually come up with new proposals and disruptive solutions using methods and approaches that are strictly connected to the discipline.

As we have seen in the previous case studies analysis, service designers work also as ‘enablers’ and ‘conveners’. Firstly, they organize training and sharing sessions, workshops and they design toolkit and/or incubators and innovation hubs, providing all the necessary resources to support innovation. And, additionally, they bring actors of the innovation ecosystem together during conferences, hackathons, jams, events, in physical spaces (such as co-working), but also in digital contexts (such as crowdsourcing platforms or other websites) (Holden et al., 2017).

But, looking more specifically at the actual tasks service designers usually carry out, it is more appropriate to refer to the Seven roles of service designers’ framework, developed by Tan between 2009 and 2012. Accordingly to the study, as the author wrote in the literature review, designers can be facilitator, innovator, capacity builder, strategist, researcher, entrepreneur or co-creator, combining together also two or more different roles.

The facilitator is in charge of translating design knowledge, methods and approaches into an accessible language to create a shared communication. Similarly, the communicator is the one who works for creating a connection in multidisciplinary teams between people from different backgrounds. He/she becomes a capacity builder when starts transfer design knowledge, methods and tools to the other field(s), something that makes possible to embed service design directly in the public sector. Service designers who act as strategists, work in a meeting position between design, planning and policy and collaborate to redefine strategic plans toward public sector delivery. The researcher is one of the most articulated roles of service designers: in this case, all the expertise on users and systems’ analysis together with known methods, are used to work out data together with other actors in the system. Entrepreneurs are in charge of developing an end-to-end development process for the innovative proposals, looking also at the business side of the system. Finally, co-creators’ role is to establish a strong connection with the public sector, that is not just about designing for it, but also involving civil servants in a participatory way to deliver new solutions (Yee, Tan, & Meredith, 2009).

On the other hand, the motivations that encourage service design to seek for collaborations with the public sector are:

- Job opportunities: the growing awareness of the potential hidden behind this successful collaboration, combined with the urgency for change that is pushing the public sector towards innovation, are creating many jobs positions, both within governments and also in external agencies. For this reason, designers are pushed to look for innovative and available jobs and, consequently, to work with the public field.

- Projects diversification: service designers are always looking for new and different challenges. For this reason, collaborating with the public sector represents the best chance they have to start diverse kind of projects and actually do something different.

- Real impact: service design is a human-based discipline. So the maximum aspiration that many designers from this gill aspire to, can only be to work for a real and deep impact that actually improves people's lives. The public sector innovation embodies the best scenario for designers who aspire to all of this.

As we have already seen in the previous chapters, the opportunities that can arise from this collaboration are many. With the intention summarizing them, citing only the most important, it is possible to say that:

- the public sector has the opportunity to easily deal and solve wicked problems, acquire new methods, skills and approach, adopt a different creative approach, rebuild citizens’ trust and gain a cost- reduction in the long-term vision;

- service design finds in the public sector a perfect field for experimentation and innovation, and has the opportunity to start challenging projects, learn how to deal with complexity, reach a large audience and have a bigger impact;

- from a mutual perspective, they both gain new knowledge, learn different skills and capabilities and have the change to embrace diverse degree of novelty in their paths.

The findings coming from the research phase, show how, if we consider the collaboration between the service design discipline and the public sector, the whole system is based on a ‘win-win strategy’. “In game theory, a win-win game is a game which is designed in a way that all participants can profit from it in one way or the other. (…) In the real world, a win-win strategy is often found in diplomacy and business, often in the form of a contract or written agreement. It’s a deal where both sides win” (Galpin, 2017). And the opportunities analysis is a clear proof of that.